The Use of AI to Assist Experts in the Analysis of Documentary Evidence

31 Aug 2023Abstract

This article discusses the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools by Experts in the analysis of documentary evidence. For this article, documentary evidence means documents discovered or otherwise provided and includes reports, emails and other business documents (that is, mainly text based documents). The application of AI frameworks like ChatGPT or other natural language processing (NLP) technologies in the legal domain, specifically for the analysis of documentary evidence, presents both promising opportunities and significant challenges. If the challenges can be overcome the opportunities presented will see significant increases in productivity for Experts. In most scenarios, documents are provided as a set of digital files; typically, not indexed. In many cases document management systems have been used to improve productivity.

What’s the Problem

Most civil legal cases involve large numbers of documents, often provided through a court direction (subpoena, notice to produce). These be complex documents with the contents semantically bound in the subject matter context. For example, documents in an IT related matter may contain significant language that relates to IT and must be interpreted in that context. Individual documents may be large, in terms of total word count, which requires significant effort to read and understand. The interconnectedness between the contents of documents may be dependent on the context of the document and the context of the matter. A number of tools currently exist (see below) which automate eDiscovery and provide a controlled framework within which a litigation team can review and analyse documents. Some of the tools offer analysis tools which include named entity recognition. The ideal “solution” is that an Expert could train an AI tool to read each document and provide analysis of the contents based on (a) the context of the specific legal matter; (b) the context of the document subject matter area; and, (c) the perspective of the Expert. The training would be iterative such that the analysis is recursively refined following feedback from the Expert. The result would be a more focussed analysis through the perspective of the Expert.

Advantages:

The availability of such a tool has some key and obvious advantages. These are typically driving productivity of the Expert and include:

- Efficiency: AI can sort through large volumes of data faster than a human can, reducing the time and manpower needed.

- Accuracy: By setting specific parameters, AI tools can identify key information consistently without getting tired or distracted.

- Interconnectedness: AI can potentially identify relationships and patterns within the data that might not be immediately apparent to human analysts. Further AI can present these relationships in many ways including graphical representations such as network diagrams and thematic maps.

Challenges:

There are some obvious challenges with an AI approach. These include:

- Complexity: Legal documents often contain language and concepts that are complex and specialised, making it difficult to program an AI tool to understand them fully.

- Context and Semantics: Legal arguments often rely heavily on context, which can be difficult for an AI tool to grasp. A single sentence can change meaning significantly depending on the surrounding text and/or the subject matter area. This context is multidimensional and could include:

- Context of the specific matter - perhaps defined by the relevant filings.

- Legal and jurisdictional context – the relevant legislative instruments.

- Context of the subject matter – for example a particular industry or sector of an industry.

- Context of the Expert – the specific area of expertise of the Expert and their understanding of that subject area. This is of particular importance due the requirement that expert evidence be fundamentally, the opinion of the Expert.

- Transparency and Accountability: An Expert must be able to demonstrate how an opinion has been reached. Often this includes taking the audience on a journey of the evidence and how such evidence supports the Expert’s opinion.

- Ethical and Legal Concerns: The use of AI in legal decision-making will raise concerns about bias, accountability, and data privacy.

Practical Approaches:

- Training the AI: The AI tool could be trained or fine-tuned using a set of legal documents that are relevant to the case at hand. Ideally these would be the pleadings (and the defence). This way, it becomes more sensitive to the language, concepts, and context specific to the case. Further the knowledge and expertise of the Expert would contribute to the AI knowledge base. That is, the model could be trained to view documents from a particular perspective (that of the expert).

- Query-based Analysis: Experts could interact with the AI system to pose queries related to the case, refining the AI’s understanding and improving the relevance of its output. This is akin to the ChatBot model such as is used by tools like ChatGPT and Bard.

- Annotation and Feedback Loop: Experts could manually annotate a subset of the documents to teach the AI system what to look for. This could also be a part of a feedback loop where the AI learns from the corrections and insights provided by experts.

- Output: The AI system could produce outputs which highlight key findings, indicate confidence levels for those findings, and show how different pieces of evidence are interconnected. The output could represent the relationships in many ways including graphical representations such as network diagrams and thematic maps.

- User Interface: A well-designed interface can facilitate effective human-AI interaction, making it easier for the expert input data, pose queries, and interpret the AI’s output.

- Transparency and Auditability: Being able to trace back the AI’s decision-making process is crucial for ethical and legal compliance. This is particularly important where some of the output of the tool is tendered as evidence.

Document Analysis – what does this mean?

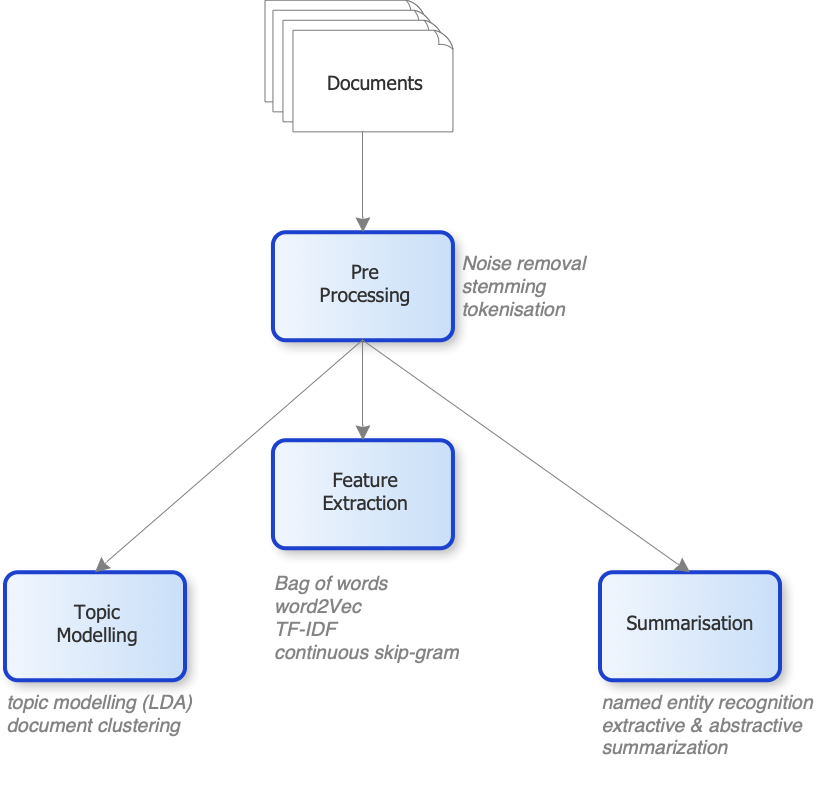

Current models of document analysis follow a general process similar to:

Pre-processing is typically the first step and may be used to:

- Correct data errors – these may have arisen as a result of OCR errors. From a legal perspective, cleansing needs to be carefully checked as misspellings and typographic errors may be significant, especially where transcripts and quotes are included.

- Removal of noise - words like “the”, “a”, and “to” are almost always the terms/tokens with the highest frequency in most documents.

- Stemming and lemmatization are the reduction of words to their root form (for example “helping” to “help”).

Feature Extraction is the process of transforming the cleansed data into a form which can be understood by the AI algorithms. There are many techniques used here including Bag-of-words (occurrence of words in a document), TF-IDF (term frequency -inverse document frequency) which describes how important a term is within a document or document collection.

Topic modelling uses techniques such as:

- LDA - Latent Dirichlet Allocation - LDA uses the words in a document to find topics a document belongs to.

- LSA - Latent Semantic Analysis - uses techniques such as singular value decomposition to keep documents and words in a semantic space.

- pLSA - Probabilistic Latent Semantic Analysis - similar to LSA but can be “trained” with expectation-maximisation algorithms.

- BERTopic and Top2Vec are advanced topic modelling techniques that leverage the Feature Extraction step to identify topics in documents.

- NMF - Non-negative Matrix Factorization involves the use of multivariate analysis and linear algebra algorithms to model topics and cluster documents.

- Document clustering - used to cluster documents together based on their contents.

Summarisation and Chat use techniques including

- Named entity recognition – seeks to locate and classify named entities into pre-defined categories.

- Extractive summarisation - takes out the important sentences or phrases from the original text and joins them to form a summary. It can use amongst other techniques, output from Feature Extraction to determine the importance.

- Abstractive summarisation – seeks to produce a document summary in a more readable form. There are many methodologies uses in this area. Perhaps the most relevant to us is the ontological method which informs the summarisation through the use of a domain knowledge base.

What is There Now

The integration of artificial intelligence into legal technology (often referred to as “LegalTech”) has spurred the development of various tools that can assist in the document analysis process. However, it’s essential to understand that the landscape is continually evolving, and new tools are emerging rapidly. Here is a list of the more commonly known tools relevant to this space.

- Generic LLM platforms including OpenAI’s GPT-3 or GPT-4, Google Bard etc: These can be fine-tuned for specific tasks, including legal text analysis.

- TensorFlow and PyTorch: These general-purpose machine learning frameworks can be customized for specific legal text analysis projects.

- Spacy: An open-source NLP library that can be customized for specific legal text analysis tasks. Spacy has quite good named entity recognition capabilities.

- DocLime - analyses PDF documents and allows you to query the document.

- ClarifyPDF - Summarise documents and respond to simple queries.

- AILyze - Summaries, thematic and Frequency Analysis, query

- Relativity: Often used in e-discovery for large litigation cases, Relativity uses machine learning to help sort and analyze large datasets. Relativity offers an advanced set of features and is widely recognised as a leading solution in this space.

- Everlaw: Provides cloud-based e-discovery and litigation software that uses predictive coding (a form of machine learning) to help sort through large volumes of data.

- Logikcull: Offers automated legal document management and provides quick data discovery solutions.

- ROSS: An AI tool that aims to help legal teams sort through case law more efficiently, although its focus is not solely on document analysis.

- DISCO: An AI-powered legal solution focusing on e-discovery, legal document review, and case management.

- Spellbook – focussed on contract drafting

- Goldfynch – eDiscovery and document statistical analysis

- Opentext – eDiscovery and document statistical analysis

- Nuix – eDiscovery and document statistical analysis

- Kira: Uses machine learning to extract relevant data from contracts and other similar types of documents.

- ThoughtRiver: Focuses on pre-screening contracts to assess their risks before they reach the legal team.

- LawGeex: Compares contracts against in-house policies to expedite the review process.

- Casetext: Uses AI to help with legal research, specifically in finding case law.

- Luminance: Uses machine learning to help with due diligence and compliance-related tasks.

This is a non-exhaustive list serving to illustrate that some solutions exist. Further, additional document analysis tools are emerging on an increasingly regular basis.

The Ideal Tool

So what would the ideal tool look like?

Most importantly, it will not be a public cloud based service. The system must respect any privacy or confidentiality obligations. Some documents may also be subject to data sovereignty restrictions.

The ideal tool would be based on existing AI frameworks and tools. This is because the tool will benefit from future enhancements to the framework. The operation of the tool could be:

- Load relevant legislation and precedent (cited) case law.

- Load and analyse pleadings (and defence). It is likely that this may include interaction with a human to ensure the tool “understands” the pleadings.

- Load and process the evidence documents.

- Allow the expert to interact and refine the model through, for example, a prompt based approach.

The effectiveness of the tool would be driven in part by the development of effective prompts. Creating effective prompts for the tool for the purpose of legal document analysis is a nuanced process that requires careful consideration. The tool’s capacity to generate useful responses largely depends on how questions and tasks are framed. Key considerations for developing prompts include:

Goal-Oriented Prompts: Information Extraction: Named entity recognition. “Extract all mentions of the plaintiff’s obligations from this contract.”

Contextual Understanding: information that relies on understanding a context. “In the context of mobile app development, what does this paragraph imply?”

Document Summarisation: summarise large volumes of text, focusing on key facts, arguments, or principles. “Summarise the key findings in this test results worksheet.”

Relationship Mapping: relationships between multiple documents or entities based on specified criteria. “Identify and map the relationships between these emails concerning Project X, John Smith and Jane Doe.”

Conditional and Layered Prompts: “If the document contains a force majeure clause, summarise its conditions. If not, indicate its absence.”

Provide confidence level: “How confident are you in the accuracy of your analysis of this indemnity clause?”

Specificity: “Extract all mentions of financial terms from these contracts.” “List the emails that discuss the defendant by name or alias.” “Identify any clauses in this contract that could be considered unfair or one-sided.” “Highlight any areas in these communications that may imply misconduct or unethical behaviour.”

Validate and Refine (Iterative Feedback): An expert reviews and corrects the outputs, and those corrections are used to refine future prompts.

Conclusion

AI tools have great potential in assisting with the analysis of documentary evidence in legal cases. Orchestrating these tools into a productive toolset for experts will result in significant productivity gains for the expert. Using the expert as the primary trainer would provide for the output of this system to validly and defensibly form an important piece of the expert’s opinion.